FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 22 JUNE, 2022

Civil society organizations, including the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives and Break Free from Plastic, are calling on leaders in the U.S. and Africa to stop waste colonialism—the illegal importing of waste from countries in the Global North to African nations already impacted by the waste and climate crises.

Their demand letter was first introduced at the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Basel Convention in Geneva, Switzerland, the first of a series of negotiations following the March adoption at UNEA-5 of a global, legally-binding treaty addressing the full lifecycle of plastics.

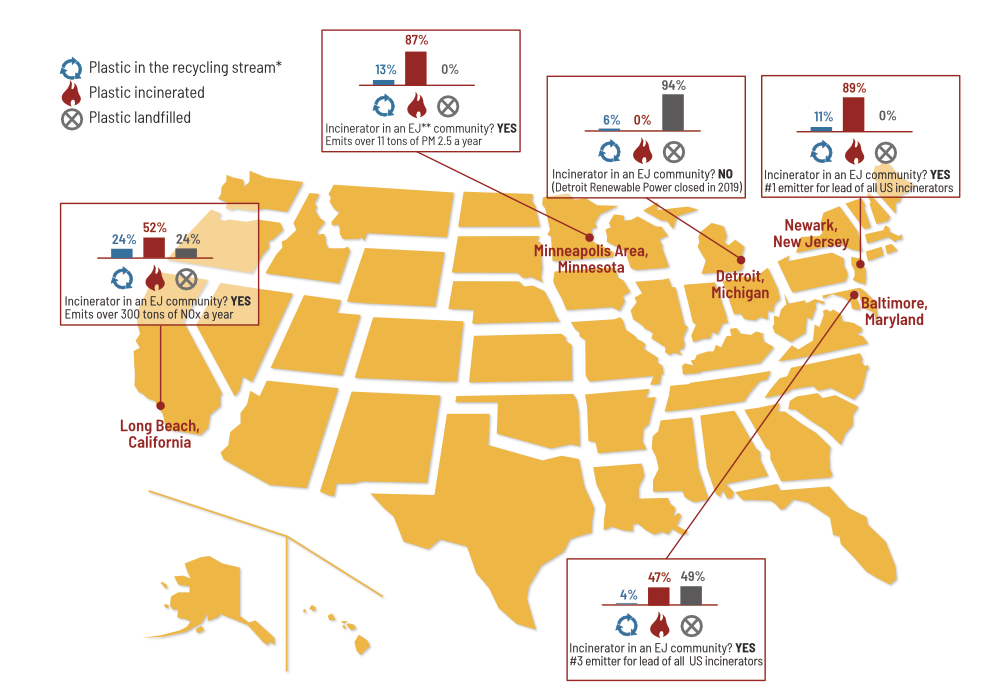

The U.S. is one of only three countries that have not ratified the Basel Convention, which prohibits the export of hazardous waste from OECD countries (primarily wealthier nations) to non-OECD countries (primarily low-income countries in the Global South). Recent research from the Basel Action Network found that U.S. ports exported 150 tons of PVC waste to Nigeria in 2021, in violation of the Convention. Many of the exporting ports are located in environmental justice communities, which like their counterparts in Africa are impacted by the waste and climate crises.

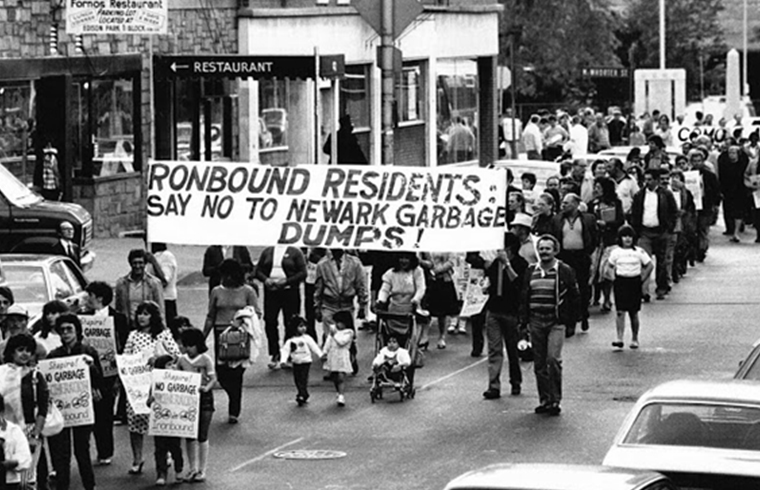

“Whatever waste is not burned in our communities is being illegally sent to relatives and grassroots partners in the global South,” says Chris Tandazo, Community Connections Program Coordinator at New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance. “Fighting for waste justice here would mean waste justice for communities in the Global South. We cannot allow the white supremacist colonial practice of dumping waste in low-income and communities of color to continue. We will continue to organize against polluting industries at home, and globally.”

Rather than stopping plastic pollution at its source, waste colonialism encourages waste management approaches that create severe health implications for workers, communities and the environment by generating significant amounts of greenhouse gases, toxic air pollutants, highly toxic ash, and other potentially hazardous residues. This includes waste incineration, chemical “recycling”, plastic-to-fuel or plastic-to-chemical processes, pyrolysis, and gasification.

“Colonialism is alive and fully functioning in the ways that waste, toxicants, and end-of-life products produced by and for overdeveloped societies move to Indigenous lands,” says Dr. Max Liboiron, director of the Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR) at Memorial University, Canada. “Without access to other people’s lands and waters, the economic systems of overdeveloped countries simply don’t work. This assumed access to other’s lands and waters is colonialism.”

“Nigeria is already overwhelmed with plastic waste—we barely have enough facilities to recycle internally generated plastics in Nigeria,” says Weyinmi Okotie, Intervention Officer of Green Knowledge Foundation (GKF) Nigeria. “I’m urging the Federal Government of Nigeria to sign the Bamako convention on toxic waste, as it will be an effective legal tool in stemming the importation of toxic wastes into Africa.”

“Ensuring that countries manage their own waste is the best way to prevent global environmental injustice. It is also essential for countries to truly come to terms with their waste footprint rather than shipping it off in containers. Once countries fully realize the absurdity of wasting precious materials and resources, harming the planet, our climate, and human health in the process, they become ready to shift to local zero waste economies centered around reuse, repair and composting of bio-waste,” says Sirine Rached, Global Plastics Policy Coordinator for the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA).

Media Contact:

Zoë Beery, Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternative

zoe@no-burn.org

For more information, see no-burn.org/stopwastecolonialism.

###

Contact

Claire Arkin, Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), claire@no-burn.org

###