May 27, 2023

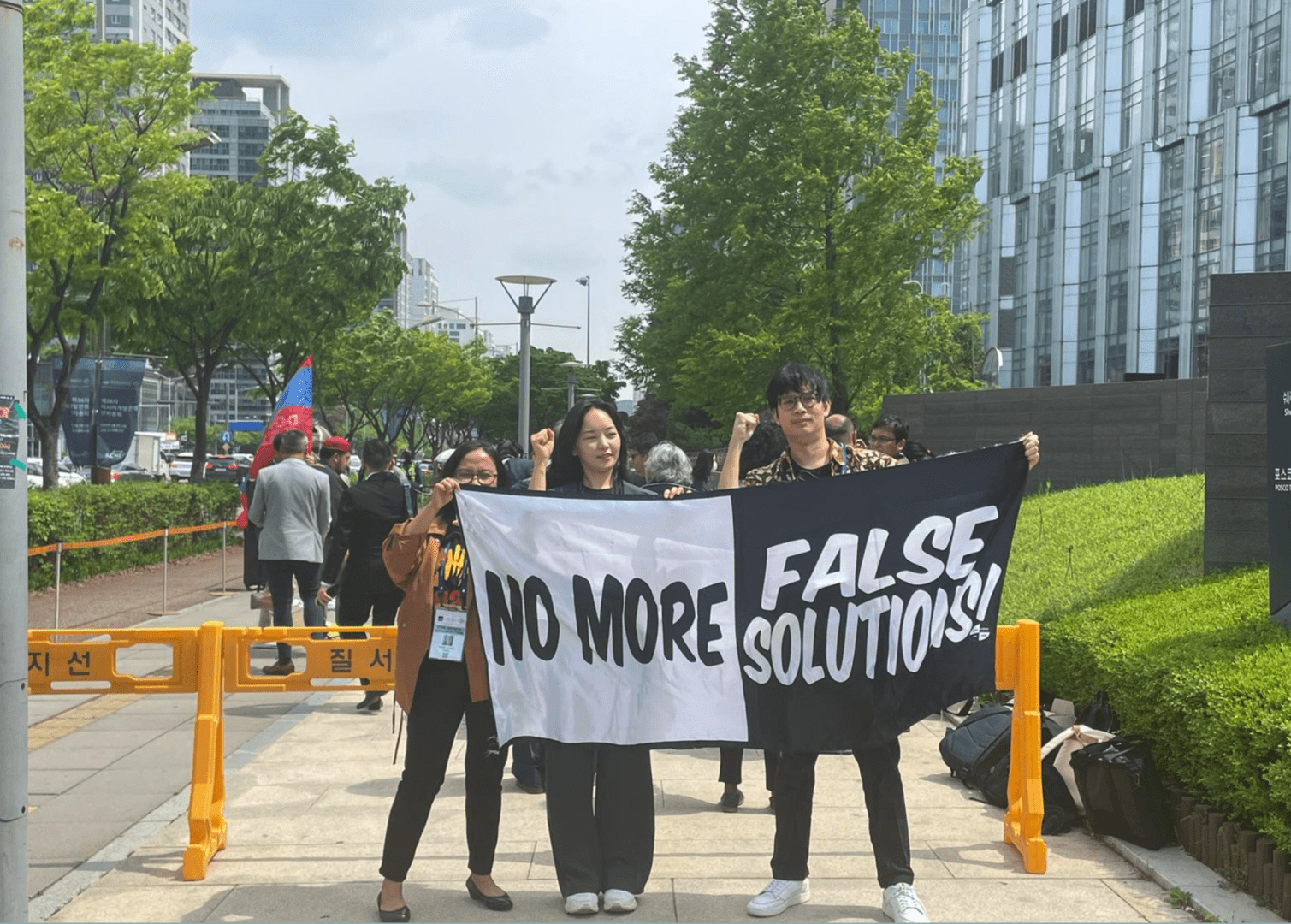

Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA) is compelled to respond to the harmful and damaging arguments published recently in The New York Times opinion piece by The Ocean Cleanup founder Boyan Slat. This article perpetuates the false narrative that the Global South is somehow to blame for the plastic pollution problem, and that expensive downstream approaches are our best tool to fight it–downplaying the necessity of reducing plastic production, which advocates and experts around the world are pushing for at the upcoming global plastics treaty negotiations next week in Paris.

One of the most egregious things this article gets wrong is the idea that countries in the Global South are the world’s largest polluters, a harmful and biased narrative that has been debunked and denounced by similarly-situated organizations focused on ocean pollution. As mentioned in the article, rich countries in the Global North are the biggest users of plastic, but this claim that they are “only responsible for 1 percent of the pollution” is far from the truth. Countries with “well-functioning systems for waste collection and disposal”–like the United States–have a paltry recycling rate while most waste is either landfilled, incinerated, or exported to developing countries. One could hardly call such a system “well-functioning.”

The narrative that this article perpetuates–that the reason waste leaks into the environment in the Global South is because of poor waste management infrastructure– lets the Global North off the hook by portraying their waste management systems as “advanced” in order to mask their shameful practices of dumping waste in the Global South. This export of non-recyclable waste to developing nations from rich countries is also known as “waste colonialism.”

For example, Latin America, which Mr. Slat names as one of the big culprits of ocean plastic leakage, has had an unprecedented surge of plastic imports from other countries. In Mexico alone, from 2018 to 2021 there was a 121% increase in plastic waste imports, 90% of it coming from the United States. Faced with an unmanageable volume of plastic garbage, there is evidence that a significant amount of these “recyclables” are being incinerated in cement kilns, an infamously dirty industry.

Similar results were found when GAIA conducted an investigation into the devastating impacts of the plastic waste trade in Southeast Asia in 2019, which found that the majority of imports were coming from the United States, Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom. These mostly contaminated, low-value bales of plastic garbage have caused horrific damage to communities in the region, including, but not limited to, health impacts from incineration, crop death, unprecedented environmental pollution, and a rise in organized crime.

In Africa, between the years 2019 to 2021 there have been several cases of waste dumping by Global North countries. This includes a case in Senegal in 2021, where a German vessel was caught trying to illegally dump 24 containers of plastic waste. In Tunisia in 2020, an Italian company illegally exported 282 containers of mixed municipal waste. Similarly, in Liberia in 2020, four containers of toxic waste had been smuggled into Liberia from Greece by Republic Waste Services, a US waste management company. And in 2019, the US exported more than one billion pounds of plastic waste to 96 countries, including Kenya.

In addition to waste exports from wealthy countries, it is a fact that the vast majority of plastic waste found in Global South lands and waterways are produced by Global North companies. Break Free From Plastic global brand audits have uncovered the same top plastic-polluting companies five years in a row–Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Nestle, Unilever, and Mondelez International .

To say that the Global South is somehow to blame for the pollution that they are forced to endure is frankly immoral and unjust. To add insult to injury, this article was published on Africa Day, 25 May, completely ignoring the historical implications and unjust power dynamics between Global North countries and countries in Africa. On that very same day, GAIA members in Africa , representing civil society groups from Tanzania, Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, The Gambia, Mauritius, Tunisia, Uganda, Cameroon, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the DR Congo, released a statement highlighting the ongoing harms of waste colonialism–this is the story that needs to be told.

The other major failing of this article is its singular focus on downstream tech-fixes as a silver bullet solution that will fix the problem. Plastic pollution doesn’t stop at the ocean. Plastic pollutes throughout its lifecycle, from extraction to disposal. The author seems to think that the goal of reducing plastic production is naive, while completely ignoring the fact that the plastic pollution crisis is a supply-side issue driven by the petrochemical companies doubling down on plastic production as a financial lifeline for losses and volatility in the fossil fuel markets.

Additionally, the author fails to account for the urgent need to reduce plastic production from a climate perspective. Plastic is made from fossil fuels, and is slated to take up 10-13% of the carbon budget by 2050. To put it bluntly, we will fail in attaining the goals of the Paris climate agreement if we do not significantly reduce plastic production, leading to climate chaos and disproportionately impacting those also on the frontlines of the plastic pollution crisis, namely the countries in the Global South that Slat has characterized as responsible.

The reduction of plastics production is within the United Nations Environment Programme’s proposal of options for elements for the plastics treaty, both in targets and implementation measures. The bans on plastic disposable items in many countries around the world, both in the Global North and South, are a demonstration that such measures can be developed by all countries, and studies show they are effective. And that is the direction that needs to be taken.

The short-sightedness of this downstream view can be evidenced in the inner workings of Slat’s own company–what happens to the plastic that is being collected by TheOcean Cleanup? Supposedly it is recycled, but as we’ve seen, most plastics are not recyclable or recycled, and even the ones that are are laden with toxics that get recycled along with the plastic resin. This hardly seems like a viable solution.

And of course, one cannot ignore the eyebrows that the scientific community has raised over the years around the technical feasibility of this grand approach. Some have raised the concern that the apparatus itself will shed microplastics, and that the net will entrap wildlife. Embarrassingly, in 2019 a giant piece of the fixture broke off, hemorrhaging millions of dollars.

The reality is that we cannot recycle or clean our way out of this plastic problem. The best way to reduce plastic pollution is to stop producing so much in the first place. It is naive to think that cleaning up rivers will be effective if we continue to produce stratospheric and increasing amounts of plastic that no country–in the Global North or Global South–will ever be able to handle. As Slat himself stated, “there is no time to waste.” At the second round of international negotiations for a global plastics treaty in Paris next week, it is critical that countries are not misled by flashy marketing but are informed by proven solutions rooted in environmental justice.

For example, as of 2019, Slat had raised over $40 million for his project, and claimed that he needed $360 million for it to work. For a fraction of what The Ocean Cleanup has already spent, groups and communities in the Global South have prevented plastic pollution from entering the ocean many times more than what The Ocean Cleanup has recovered, while even saving cities money and creating over 200x as many jobs as waste disposal.

Organizations in Africa, like Nipe Fagio, who are working with a local waste collection cooperative, Wakusanya Taka Bonyokwa Cooperative Society, demonstrate that separate collection of waste has helped to divert more than 80% of the waste generated in a low-income sub-ward of Bonyokwa, in the Ilala district in Dar es Salaam through composting, reuse, and recycling, reducing the waste to 10-20%. In South Africa, there is an estimate of 90,000 people who make a living from waste picking. They recover between 80 to 90% of the post-consumer packaging and paper which would otherwise be sent to landfill.

In Latin America the situation is similar–flagship examples are found in Brazil, Argentina and Colombia with waste picker organizations advocating for better Extended Producer Responsibility implementation, and laws that ban incineration and phase-out toxic and non-recyclable plastics. A more viable solution would be to invest in systems that better enable the informal sector rather than create infrastructure which will displace them.

The article defends the developed world’s addiction to plastic the same way that people have defended extremely harmful models in the past (slavery, colonialism) as essential to the economy. Is this the kind of world we want to fight for? GAIA and its allies are choosing hope over defeatism, accountability over inevitability, and justice over sacrifice. Now is not the time for tinkering at the margins of the crisis–it’s time to turn off the plastic tap.